- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Original reference

- Dominant lithology:

-

- Limestone

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Safford, J.M., and Killebrew, J.B., 1876, Elementary geology of Tennessee: Nashville, TN, 255 p.

Summary:

Pg. 108, 123, 130-131, 137. Lenoir limestone. Soft blue shaly fossiliferous limestone 100 to 600 feet thick. Same as MACLUREA limestone of Report on geology of Tennessee. In western part of valley, next to Cumberland Pleateau, is not separated from overlying limestone by any well-marked characters. Is of Chazy age [Early Ordovician]. Older than Lebanon [Stones River] group. Overlies the Knox dolomite.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 896, p. 1170).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Overview

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

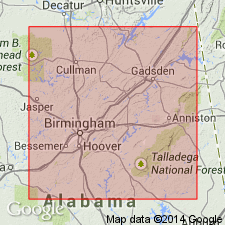

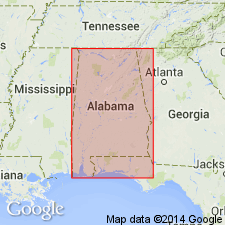

Lenoir limestone of Stones River group. Age is Early Ordovician (Chazy). Recognized in eastern Tennessee, northern Alabama, and western Virginia. Named from exposures at Lenoir Station [Lenoir City, Lenoir City 7.5-min quadrangle], Loudon Co., eastern Tennessee.

There is no conclusive evidence to show whether Mosheim limestone (Ulrich, 1911) was originally included in Lenoir limestone or in Knox dolomite. It is unconformably separated from overlying and underlying beds, and according to E.O. Ulrich and C. Butts it differs from the Lenoir in lithology, color, and fauna, but is of Chazy age, as is the Lenoir. According to A. Keith (personal commun.) all of the chertless limestones were excluded from the Knox by Safford in his definition and in his mapping.

The Lenoir is now considered by E.O. Ulrich and C. Butts to be top formation of Stones River group of eastern Tennessee and western Virginia, where it overlies Mosheim limestone, and this is adopted definition of the USGS.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 896, p. 1170).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Areal extent

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 139-147. Lenoir limestone of Stones River group. Succeeds Mosheim limestone or Murfreesboro limestone, or Beekmantown dolomite where Mosheim is absent, as in Knobs area south of Abingdon, Washington County, western Virginia. With exception of vicinity of Draper, Pulaski County, western Virginia, the Lenoir, so far as known, is universally present throughout Appalachian Valley. Well exposed at top of St. Clair facies (new) of Murfreesboro limestone in following areas [of western Virginia]: Yellow Branch, southeast of Rose Hill, Lee County; southeast of St. Clair Station west of Bluefield; northeast of Bolar, Bath County; and west edge of Crabbottom, Highland County. Where Blackford facies (new) of Murfreesboro is present, the Lenoir is not obviously recognizable but is probably present above the Mosheim. Thickness 5 feet or less at places in area of Blackford facies northwest of Clinch Mountain; 30 feet in Knobs area near Abingdon; commonly 50 feet throughout most of Appalachian Valley; possible maximum thickness 200 feet northwest of Newport, Giles County. In Stones River group. Underlies Holston limestone of Blount group. [Age is Middle Ordovician.]

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Not used

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 819-886. Lenoir limestone. Lower Middle Ordovician succession of Tazewell County, southwestern Virginia, is subdivided into 29 distinctive zones which are grouped into eight formations. Study led to recognition of inconsistencies in use of names Stones River, Murfreesboro, Mosheim, Lenoir, Blunt, Holston, Ottosee, Lowville, and Moccasin. Lenoir limestone of Butts has been identified largely on basis of its superposition with respect to beds supposed to be Mosheim, resulting in identification of two different zones as Lenoir. In proposed revised stratigraphic nomenclature, Cliffield formation (new) includes beds which Butts has called Murfreesboro, Mosheim, Lenoir, Holston, and Ottosee.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Overview

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 35-114. In classifying lower Middle Ordovician of Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, formation names Stones River, Mosheim, Lenoir, Holston, Whitesburg, and Athens have been used without adequate evidence. The Lenoir and Mosheim limestones have been misidentified in much of the Appalachian Valley of Virginia, and confusion regarding these formations has resulted in misidentification of many of the succeeding formations. Therefore, relationship of type Lenoir to type Mosheim has been restudied. In limestone belt which passes through Lenoir City and Philadelphia, Tennessee, type Lenoir directly overlies Knox dolomite and exhibits three-fold development. Lower 15 to 25 feet composed chiefly of mealy-weathering dolomitic mudrocks with intercalated beds of dove-gray calcilutite; middle division, 25 to 45 feet thick, is impure limestone containing MIMELLA NUCLEA (Butts), distinctive but undescribed species of VALCOUREA and HESPERORTHIS, and characteristic coral BILLINGSARIA PARVA; upper 100 to 125 feet is dark-gray medium-grained sparsely cherty limestone with MACLURITES "MAGNUS" the only common fossil. Southwest of Philadelphia, limestones of lower division of Lenoir grade vertically and laterally into dolomitic mudrock. In type exposures of Lenoir, 4 to 9 feet of dove-gray limestone, not unlike beds elsewhere called Mosheim, occur at base of Lenoir and are overlain by 7.5 feet of dolomitic mudrock. Basal Lenoir calcilutite and these mudrocks are separated by 2 to 18 inches of shaly limestone containing abundant ROSTRICELLULA PRISTINA (Raymond). Lithologic similarity, stratigraphic position, and occurrence of this fossil correlate lower dolomitic division of typical Lenoir with lower Blackford of Virginia. If calcilutite at base of type Lenoir were to be called Mosheim, the identification would have to be based wholly on lithologic resemblance which is not very pronounced. Near Friendsville, Tennessee, where Lenoir is prominently displayed, Mosheim-type limestone occurs at several horizons. Northeast of Friendsville, where lower "Mosheim" zone is developed, the lower dolomitic division of typical Lenoir is absent, and basal calcilutite is overlain by middle fossiliferous division of the Lenoir. These "Mosheim" beds may be a dove limestone facies of lower Lenoir. Since real Lenoir contains more that one intercalation of dove-gray calcilutite and since substantial part of lower Lenoir seems to be supplanted by this type of limestone, it is believed that beds with "Mosheim" lithology are a facies of the typical Lenoir. Probably type Mosheim is a calcilutite facies representing substantial part of typical Lenoir. Use of name Mosheim for a pre-Lenoir stratigraphic division should not be extended hundreds of miles away from type locality when evidence that the Mosheim underlies the Lenoir is lacking in critical localities. Butt's Lenoir in northern Virginia is apparently not represented in Lenoir of type locality. In proposed reclassification, the lower Middle Ordovician is divided into six time-stratigraphic units (ascending): New Market limestone, Whistle Creek limestone, Lincolnshire limestone, Edinburg formation, Oranda formation, and Collierstown limestone. At least part of New Market limestone is linked with part of New York Chazy and type Lenoir.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 1181-1182. Lenoir limestone. Discussion of lower Middle Ordovician of southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee. Measured sections compared with revised classification in Tazewell County, Virginia. Lenoir limestone was named by Safford and Killebrew for nodular argillaceous MACLURITES-bearing limestone at Lenoir City, Tennessee. They considered it to be same as MACLUREA limestone. Since this was defined as occurring above Knox dolomite (Beekmantown) and below the Marble ("Holston" marble), it is likely that this is definition intended at Lenoir City. This would here include "Mosheim" (Five Oaks) limestone at base. Since the naming of "Mosheim" in 1911, the Lenoir bas been generally considered of post-"Mosheim", pre-"Holston" age. Though upper Lenoir in type section is covered, outcrops nearby show typical Lenoir lithology to continue to base of "Holston." Under strict analysis of original designation, the boundaries are not sufficiently definite to preserve validity of name. In view of its wide use, name should be retained but should be redefined. Lenoir may be defined as the argillaceous nodular limestones occurring between "Mosheim" (Five Oaks limestone) and the "Holston" (Farragut limestone, new). Northwest of Clinch Mountain, the Lenoir would occur chronologically between the Five Oaks and Thompson Valley (new) limestones. The Five Oaks is commonly absent in both areas, and, where Blackford formation is absent, the Lenoir rests directly on the Beekmantown. Age is Middle Ordovician.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Areal extent

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

(and 1954, Virginia Geol. Survey Bull., no. 71, p. 84-90). Lenoir limestone. In Rose Hill oil field, Lee County, western Virginia, Lenoir overlies Mosheim limestone and underlies Lowville limestone. Lenoir of Rose Hill area is about same as Lenoir of Butts in southwest Virginia and probably correlates with Lincolnshire of Cooper and Prouty in Tazewell County. Age is Early Ordovician.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir (Ridley) limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Areal extent

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 22, 25-26, geol. map. Lenoir (Ridley) limestone included in Stones River group in northwestern GA. Thickness about 100 feet. Overlies Mosheim limestone; underlies Lebanon limestone.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone*

- Modifications:

-

- Mapped

- Dominant lithology:

-

- Limestone

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Areal extent

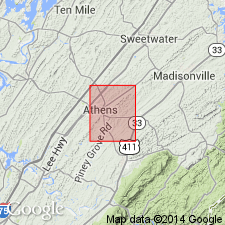

Summary:

Lenoir limestone, in Athens quadrangle, consists chiefly of dark bluish-weathering argillaceous nodular limestone; basal beds, which rest unconformably on Mascot dolomite, vary from place to place. Massive aphanitic limestone, comparable to Mosheim limestone near Knoxville, is present locally in Sweetwater Valley and in extreme southeastern part of area. It is as much as 15 feet thick just south of southeast corner of quadrangle. In other places, basal beds are greenish silty dolomitic limestone containing angular chert fragments. Both rock types appear to be lateral facies of typical Lenoir limestone. Lenoir in Athens area was mapped as Chickamauga by Hayes (1895, Folio 20); however, name Lenoir has priority as applied to these rocks, and typical Chickamauga includes beds equivalent to Ottosee shale and higher formations. Thickness about 250 feet in Sweetwater Valley; 40 feet elsewhere. Contact with overlying Athens shale gradational. Age is Middle Ordovician.

Source: Publication; US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 68-78, pls. Lenoir limestone. In this report, the Mosheim is considered a member of the Lenoir and locally replaces the lower part of the formation. The Lenoir underlies the Holston formation and overlies Knox group. Lenoir limestone and Athens shale grade into each other in vague belt near Monroe-McMinn Co. line, eastern Tennessee. [Age is Middle Ordovician.]

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone*

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

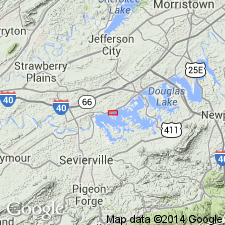

Pg. 727-729. Lenoir limestone. In Douglas Lake area, includes Douglas Lake member (new) in lower part. Overlies Mascot dolomite Underlies unnamed shaly limestone. [Age is Middle Ordovician.]

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone*

- Modifications:

-

- Mapped

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Lenoir limestone. Lenoir, in Shooks Gap quadrangle, Tennessee, divided into Mosheim member at base and main body of Lenoir. Thickness 380 to 500 feet. Underlies Holston formation; unconformably overlies Newala formation. Age is Middle Ordovician.

Source: Publication; US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone*

- Modifications:

-

- Areal extent

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 145 (chart), 147-148, pl. 28. Term Lenoir limestone is applied in this report [Tellico-Sevier belt, eastern Tennessee] to limestones of several distinctive types that comprise basal part of Middle Ordovician section. Main part of formation consists of gray cobbly argillaceous limestone with which name Lenoir is associated by many geologists from Virginia to Alabama, regardless of exact stratigraphic position or fossil content. Also included is dove-gray aphanitic limestone termed Mosheim member, and a discontinuous basal unit characterized by several kinds of detrital limestone to which term Douglas Lake member is applied. Wherever there are exposures, the Lenoir, 26 to 95 feet thick, intervenes between basal beds of Blockhouse shale (new) and highest beds of Knox group. This fact is emphasized because Keith (1895, folio 16; 1896, folio 25) showed Athens shale resting on Knox in most places.

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Pg. 72. Lenoir limestone. Name Lenoir restricted to sequence exhibited at type locality on east side of Lenoir City, Loudon County, eastern Tennessee. So restricted, the sequence containing CHRISTIANIA, originally referred to the Lenoir by many geologists, is excluded. CHRISTIANIA beds are herein named Arline formation. At type locality, the Lenoir contains three zones (ascending): ROSTRICELLULA, VALCOUREA-MIMELLA, and MACLURITES. Best development of Lenoir is at Friendsville, Blount County, eastern Tennessee, where each zone is fairly thick. To the west of Friendsville area, across strike of various belts, the Lenoir changes lithology and is ultimately cut out. In its changed lithology, the Lenoir appears as a calcarenite well exhibited near Tumbez in Virginia with basal conglomerate containing ROSTRICELLULA, and massive limestones above it contain VALCOUREA and MIMELLA. Hence, it has been called Tumbez formation (Cooper, 1945). Blackford formation of dolomites, red beds, and conglomerates is equivalent to Tumbez and Lenoir. In belt along Cumberland Front, the Lenoir is missing; Blackford facies (Dot formation) there is equivalent to Hogskin member of Lincolnshire formation. [Age is Middle Ordovician.]

Source: US geologic names lexicon (USGS Bull. 1200, p. 2148-2151).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir Limestone*

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- Dominant lithology:

-

- Limestone

- Dolostone

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Cottingham Creek Member of Lenoir Limestone named at Pratt Ferry, AL. Occupies a paleotopographic low (karst feature) in Newala Limestone of Early Ordovician age. Lowest unit in Lenoir Limestone at type section of Cottingham Creek. "The base of the member consists of recrystallized conglomeratic dolostone containing pebbles, cobbles, and boulders of lime mudstone, packstone/grainstone, and dolomudstone. The clasts are as much as 30 cm in diameter and all appear to have been derived from the Newala Limestone. The basal conglomerate is overlain by various types of dolostone, including dark-brown, bryozoan-rich dolowackstone and dolomudstone, burrowed dolomudstone, and greenish-gray dolosiltite. Cross-bedding is well developed updip and at the base of the unit. The uppermost part of the member is a thick-bedded, massive, sandy, argillaceous, brownish-gray dolostone that is laterally continuous across the depression." Megafossils are predominantly bryozoans but include brachiopods and gastropods. Maximum thickness uncertain because base of paleotopographic low extends beneath the Cabaha River. Estimated to be 16 m. Probably correlates with the Douglas Lake Member of Lenoir Limestone in TN. Overlies Newala Limestone; underlies Mosheim Member of Lenoir Limestone. Age is Middle Ordovician (middle to late Whiterockian).

Source: GNU records (USGS DDS-6; Reston GNULEX).

- Usage in publication:

-

- Lenoir Limestone

- Modifications:

-

- Revised

- AAPG geologic province:

-

- Appalachian basin

Summary:

Immediately overlying the Mosheim Limestone Member of the Lenoir Limestone in the Cahaba Valley of AL are a few feet of distinctive light- to dark-gray coarse-grained limestone (grainstone) composed of skeletal fragments, intraclasts, peloids, and occasional ooids, referred to as the Lee Branch Member by Roberson (1988) in an unpublished University of AL M.S. thesis. The Lee Branch generally ranges from 3 to 6 ft thick, but at Shephard Branch is less than 1 ft. Age is Middle Ordovician (Whiterockian).

Source: GNU records (USGS DDS-6; Reston GNULEX).

For more information, please contact Nancy Stamm, Geologic Names Committee Secretary.

Asterisk (*) indicates published by U.S. Geological Survey authors.

"No current usage" (†) implies that a name has been abandoned or has fallen into disuse. Former usage and, if known, replacement name given in parentheses ( ).

Slash (/) indicates name conflicts with nomenclatural guidelines (CSN, 1933; ACSN, 1961, 1970; NACSN, 1983, 2005, 2021). May be explained within brackets ([ ]).